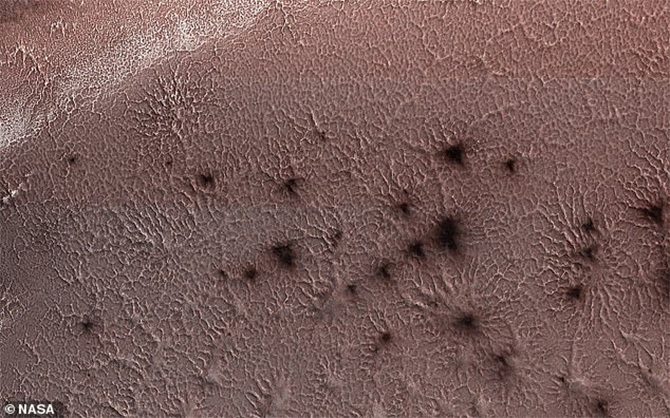

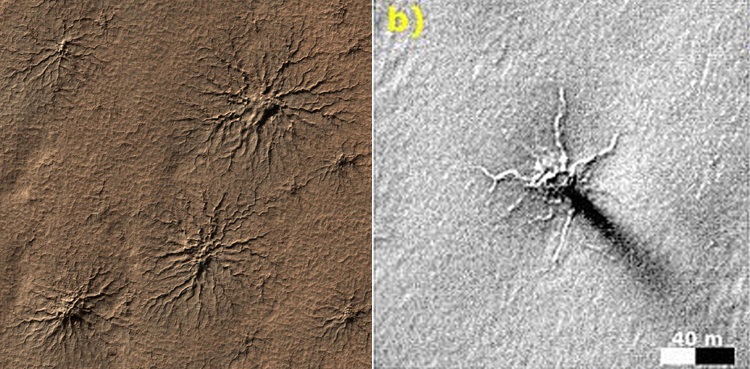

The astronomers have solved the mystery of ‘Spiders from Mars’ resembling creepy black arachnids that were first observed 20 years ago as they are caused by carbon dioxide vapor escaping from cracks in polar ice during the Martian spring.

Astronomers have determined that ‘araneiforms’ (Latin for ‘spider-like’) are actually caused by carbon dioxide vapor escaping from cracks in polar ice in the spring. The latest finding makes researchers to nail down the suspected hypothesis by recreating conditions from the surface of Mars in a simulator.

They observed the same spindly patterns emerge on the surface after lowering and lifting blocks of dry ice—essentially frozen CO2—onto beds of gravel, Dailymail UK reported.

When sunlight reaches through the translucent ice covering Mars’ poles each spring, it warms the loose rock below and builds up pressure. That pressure causes the ice to crack and vaporized carbon dioxide to escape forcefully, blasting sand and grit into the air.

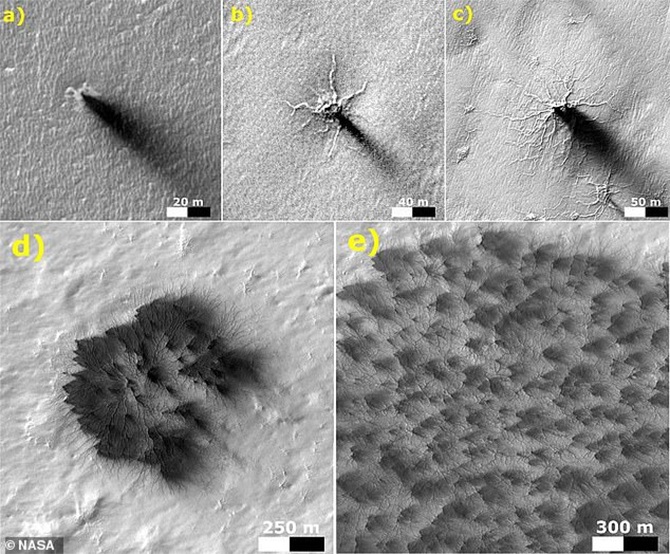

The granular material then settles on top of the ice in shapes that resemble tree branches or spindly spider legs. The pressure is so strong the CO2 actually sublimates, or transitions directly from a frozen solid to vapor.

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and other satellites have captured araneiforms, and the theory that they’re caused by escaping CO2 ‘has been well-accepted for over a decade,’ said Lauren McKeown, a researcher at the Open University and lead author of a study published in Scientific Reports.

‘But until now, it has been framed in a purely theoretical context,’ she added.

McKeown and colleagues from Ireland and the UK recreated Martian atmospheric pressure in the Open University Mars Simulation Chamber in Milton Keynes, England in order to test the theory.

They drilled holes in blocks of dry ice, the solid form of carbon dioxide, and suspended them above beds of various size granules. The pressure in the chamber was lowered to approximate the atmosphere on Mars, then the dry ice was lowered onto the sandy surface.

When the block reached the surface, the CO2 turned directly from solid to gas and vapor escaped through the hole. In every experiment, when the block was lifted, a spidery pattern was left behind.

The finer the sediment used, the more branches the patterns had, the authors reported. ‘The experiments show directly that the spider patterns we observe on Mars from orbit can be carved by the direct conversion of dry ice from solid to gas,’ McKeown said.

Araneiforms, which can span up to 3,300 feet across, aren’t found anywhere on Earth.

That’s because there’s so much less carbon dioxide on our planet: The atmosphere on Mars is more than 95 percent CO2, which also comprises much of the ice and frost that forms at the Martian poles in winter.

McKeown called the discovery ‘exciting,’ because scientists are finally beginning to understand more about how the surface of Mars changes each season.

The findings could also be useful to NASA, which has targeted human missions to Mars for the 2030s.

A geomorphologist at Trinity who supervised the research, Mary Bourke said, ‘This innovative work supports the emergent theme that the current climate and weather on Mars has an important influence not only on dynamic surface processes, but also for any future robotic and/or human exploration of the planet.’

Leave a Comment